Horse's Canter Movement

The canter is the most expressive and — when properly executed — most beautiful of the standard gaits. While some make a distinction between the canter and the lope, most people use the term lope for the western equivalent of the canter. In both instances, it is a three-beat gait.

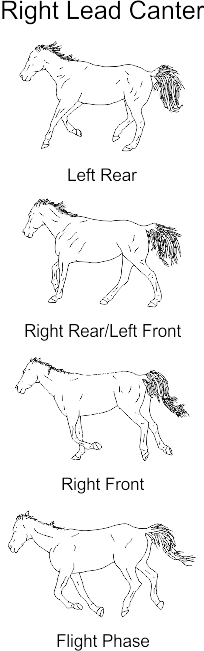

The canter or lope is made up of three footfalls followed by a period of suspension. One hind foot first strikes the ground. This is followed by the opposite hind foot and its diagonal forefoot. Then comes by the other forefoot. The horse pivots its body over this foot. It then glides through the air and regroups its legs to begin the next stride of the canter.

The canter is said to be performed in a right or a left lead. The right lead is initiated by the left rear foot striking the ground. This is followed by the right rear and left front moving in unison. Finally, the right front foot reaches out taking the weight of the body. The horse's body pivots over this foot and glides through the air before the sequence of steps repeats itself. The left lead is initiated by the right rear foot, followed by the left rear/right front diagonal, and, finally, the left front. When cantering circles, it is easiest on the horse and smoother for the rider to canter the right lead when going clockwise (on the right rein) and the left lead when going counter–clockwise (on the left rein).

Many consider that the lead as being determined by the front foot which the horse pivots over. I prefer to think of the alignment of the horse's shoulders and hips. In the right lead, the horse's right shoulder and right hip are held slightly in advance of its left shoulder and hip. In the left lead, the left shoulder and hip are held in advance of the right shoulder and hip. This is much the same as a humans hip alignment when skipping.

I once heard a young girl experiencing her first canter, yell: "I'm flying. I'm flying." She was, in fact, flying during that period of suspension between the last footfall of the one sequence of steps and the beginning of the next. The height and length of that gliding flight is determined more by the impulsion of the horse than by the quickness of its movements.

Some describe the canter as the fastest of the standard gaits aside from the gallop. But it is the sequence of footfalls, not the speed, which establishes the canter. Some horses can canter with a slower forward motion than others trot. A few horses have even cantered in place or even to the rear, though this "canter" usually takes on a four–beat rhythm.

A horse's inside hind leg provides most of the trust required in the canter movement. Horse's commonly avoid this extra effort by carrying their hindquarters to the side, especially in one lead. See the section on lateral movements for information on exercises designed to eliminate this evasion.